Local Spotlight

by Kristen E. Humphrey, MLA, Local Assistance and Training Planner with Graham Dodge, Executive Director, MAGIC

Planning Practice Monthly has been reporting for some time on the advent of connected and automated vehicle (CAV) technologies and the Statewide CAV Working Group’ s efforts to begin planning for new modes of transportation that will likely include driverless and/or self-driving vehicles in the not-so-distant future. (Visit our archives webpage to read additional CAV coverage.)

It’s one thing to discuss implementing CAV technologies; however, it’s an entirely different story to craft policies and regulations for adopting them, much less to identify and construct new infrastructure to make their use viable and safe. So, what are the steps involved? How does a jurisdiction begin to understand and plan for technologies that still feel distant and futuristic, but are seemingly inevitable and just over the horizon?

In partnership with the Maryland Department of Transportation’s (MDOT) CAV team, Planning staff reached out to Graham Dodge, Executive Director of the Mid-Atlantic Gigabit Innovation Collaboratory (MAGIC), a non-profit organization located in Westminster. MAGIC is striving to unravel the complexities of CAV issues and technologies and to develop the first municipal CAV plan in Maryland. Below is a recap of our conversation:

First, tell us about MAGIC? How did Magic get involved in this project?

MAGIC is a 501(c)3 nonprofit working to build tech communities through cutting edge innovation, entrepreneurial incubation, and public education. MAGIC’s mission, as stated on our website, is “to build a tech ecosystem that creates and nurtures talent, entrepreneurship, and tech businesses, elevating the Westminster Gigabit Community to lead the Mid-Atlantic region. We strive to make the Westminster Gigabit Community a premier technology hub in the Mid-Atlantic region.”

To fulfill this mission, we are building relationships between educational institutions in Carroll County, the tech community, and partners in the corporate and local government sectors. We offer learning opportunities for high school to college-aged students as well as workforce development for adults interested in joining the technology field. MAGIC is a CAV Working Group member and is serving as the lead project manager in the development of Westminster’s plan.

What is the CAV plan and who will it serve (residents, businesses, local governments fleets)?

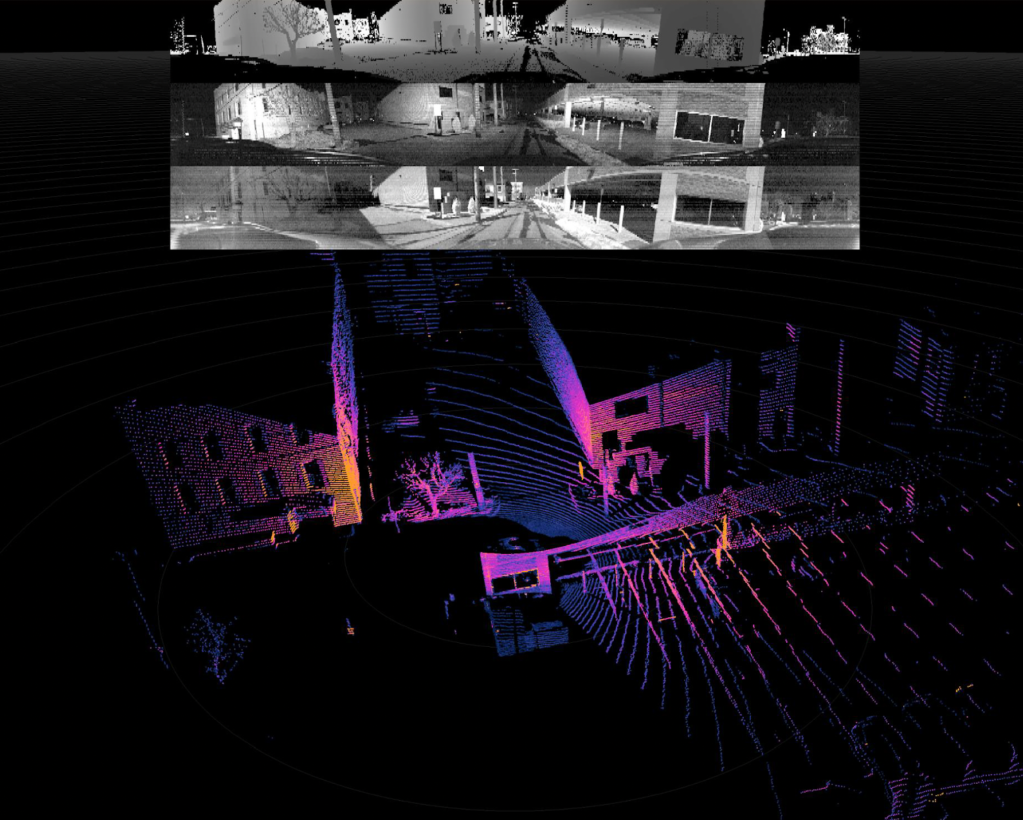

Our plan is called the Westminster Autonomous Corridor project. It has several phases of development. Phase One has been completed and involved both aerial and ground LIDAR scanning, as well as market research, feasibility analysis, and promotional kick-off (see description of LIDAR technologies in sidebar,

right). The scanning of several city routes will be used to train autonomous shuttles to operate on Westminster’s specific topography, and in response to all-weather road conditions and traffic patterns.

Phase Two will deploy sensors and create a digital twin asset (a virtual copy of a real-life setting or “asset,” such as a piece of machinery, a building or, in this case, an entire city) to which the autonomous systems and sensors will connect once activated. According to Dodge:

A digital twin in this case works by providing the autonomous systems a virtual version of the city in which they can be trained, either as the operating system interacting with the digital twin or as the entire hardware system interacting remotely through a ‘hardware in the loop’ set-up.[1]

In the latter case, the vehicle or hardware is stationary at a remote location but thinks it’s in the operational design domain (ODD), while interacting with the digital twin. This allows these systems to be fully trained on their intended environments before the rubber ever meets the road. Once deployed, the digital twin then provides a continuous ‘God’s eye view’ of the city in real time.” [2]

Phase Three and beyond will expand the digital twin infrastructure and deploy live autonomous systems. It will initially serve academic research and development partners, municipal data collection and baseline monitoring needs, and eventually will serve citizens and businesses through the response of “actionable data insights” (i.e., data-informed, real-world decisions, such as policies and regulations), adaptive smart-city technologies, and autonomous transportation.

What are the perceived needs for CAV planning in the community and what are the goals and projected outcomes of this plan? Have they changed/evolved since conception?

The primary needs included transportation gaps – the result of needs not met by prevailing forms of private or public transportation – experienced by residents, students, and visitors to Westminster. These have evolved to include various municipal functions of the city and its corresponding agencies.[3]

Some departments that may be able to take advantage of a digital twin include public works, public safety, zoning, and planning. Some applications of the technology might address monitoring road and pedestrian hazards, vegetation encroachment and tree health, or smart, adaptable streetlights for improving traffic flow, and reducing idling time.

In terms of identifying and responding to transportation gaps, the greatest support for the project has come from the special needs community. Organizations like The Arc of Carroll County, Spectrum Support, Inc., and Penn-Mar Human Services, have all written letters of support for the autonomous corridor project to serve the transportation needs of their clients. Additionally, other organizations that support the special needs community like Carroll County Public Schools and the Boys and Girls Club of Westminster have also written letters of support for the project. Finally, McDaniel College and Carroll Community College have and continue to support the project for the academic research and development opportunities it provides their own students.

Who are the key partners (community groups, non-profit organizations, local and state agencies) involved with this effort? Is there a lead group?

Although MAGIC is serving as the lead project manager on the Corridor project, Dynamic Dimension Technologies (DDT), a Westminster-based digital twin software development company (and fellow MDOT CAV Working Group member) is the main contractor supporting the project. They have donated more than $100k of in-kind LIDAR scanning and software development services for Phase One of the project.

The Carroll Composite Squadron of the Civil Air Patrol has also provided valuable in-kind support for aerial drone scanning of the city and coordinated the permitting process through the FAA and U.S. Air Force. The City of Westminster is taking an increasing role in planning and budgeting in anticipation of a budget vote by its City Council this month that will potentially fund Phase Two of the project.

Last but not least is Vince Brusio, a realtor for the Eldersburg Coldwell Banker Realty who sits on the Carroll County Transition Council, who helped gather letters of support from the special needs community.

How has the state or Maryland Department of Transportation assisted?

The CAV Working Group has provided valuable networking and support from its members. Meanwhile, MDOT helped us initiate collaborative discussions with the State Highway Administration (SHA) and the Maryland State Police when planning our autonomous vehicle testing for a showcase event, which was conducted in May 2021, as part of the Highly Automated Vehicles (HAV) permitting process. MDOT continues to share valuable information, funding opportunities, and updates as we continue to develop our project.

How long have these efforts been in the works, from initial concept until the present?

We started imagining this project with DDT in late 2020 after visiting and test driving the Olli at Local Motors in National Harbor. By December 2020 we had submitted an Expression of Interest to MDOT and joined the CAV Working Group.

What was (or what do you anticipate may be) the largest hurdle to overcome in this process?

Fundraising and the budget justification remains the biggest challenge, despite the in-kind support, given the high cost of acquiring, leasing, and deploying autonomous shuttles for public use. The next biggest challenge will be deciding who will manage the first CAV fleet in the city, whether that be the city under a new transit authority, individual partners and stakeholders like our local colleges, our county transit operator, or a third-party integrator like Beep or First Transit.

Is there a projected launch/publication date for the plan? What is the expected timing for the first big milestone?

The next big milestone will be when the Westminster City Council votes on the proposed budget for Phase Two of the project (May-June 2022). If approved, it will kick off development of the digital twin in July, which could create a positive domino effect of research and development projects coming to the city.

What types of related developments do you foresee this project/plan sparking in the future? In which of these might your agency and/or the lead stakeholder participate?

We foresee the infrastructure that this project will build as “futureproofing” for various autonomous transportation needs, including freight, drone, and Vertical Take Off and Landing (VTOL) personal aircraft[4]. Potential use cases and development of the digital twin for the City of Westminster alone are numerous. These opportunities may include deploying and connecting adaptive traffic technologies and environmental sensors that inform detailed simulations for planning, emergency response, and civil engineering efforts.

Lastly, it remains to be seen how the digital twin asset could become an entry point for virtual tourism and entertainment production as a foray into the Metaverse[2], but an early example of this can be found in Helsinki’s digital twin project that created a detailed 3D model of the entire city. This was then imported into the game of Minecraft for both players and for use in as prototype civil engineering projects.

What lessons learned would you share with other communities and stakeholders seeking to embark on a similar program/plan?

Look for industry sector and academic interdependency within your region that can support the ongoing research and development of your project. Also, look for the end users who will benefit the most from your project, whether they are city officials, public safety officers, or various resident demographic groups. You should then seek grant funding that aligns with each of those segments. Finally, create a phased and measured approach that is sure-footed, as opposed to the quick, easy path. You are dealing with emerging technologies that haven’t fully matured yet and that come with liabilities and risks, and that means you will need to develop assurance and trust over time to be impactful, actionable, and useful.

For more information about CAV technologies in Maryland, please visit MDOT’s CAV website. If you would like to be added to the mailing list for future meetings of the Maryland CAV Working Group, please email CAVMaryland@mdot.maryland.gov.

[1] Hardware in the loop (HIL) testing is “a technique where real signals from a controller are connected to a test system that simulates reality, tricking the controller into thinking it is in the assembled product. Test and design iteration take place as though the real-world system is being used. You can easily run through thousands of possible scenarios to properly exercise your controller without the cost and time associated with actual physical tests.” Source: https://www.ni.com/en-us/innovations/white-papers/17/what-is-hardware-in-the-loop-.html.

[2] To create CAV technologies that operate safely involves “understanding [various] ‘conditions’ in which the CAV is capable of operating safely. The CAV industry calls these ‘conditions’ — the Operational Design Domain (ODD). For example, the operating conditions (ODD) of a low-speed shuttle could include a city centre or a business park, but not a four-lane highway.” Source: https://medium.com/@siddkhastgir/the-curious-case-of-operational-design-domain-what-it-is-and-is-not-e0180b92a3ae.

[3] For more information on the issue of transportation gaps, view research presentation by McDaniel College Environmental Studies student, Molly Sherman, entitled Transforming Westminster with Public Transportation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9d3ld-rlj2s.

[4] A vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft is a vehicle that can depart, hover and land vertically. This includes fixed-wing aircrafts with the ability to take off and touch down vertically as well as helicopters or other aircraft with powered rotors. Source: https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/definition/vertical-takeoff-and-landing-VTOL-aircraft.

[5] There is no one definition of the term Metaverse. However in simple terms, one source states “In the broadest terms, the metaverse is understood as a graphically rich virtual space, with some degree of verisimilitude, where people can work, play, shop, socialize — in short, do the things humans like to do together in real life (or, perhaps more to the point, on the internet).” Source: https://www.polygon.com/22959860/metaverse-explained-video-games.

Pingback: Update: Connected and Automated Vehicle (CAV) Planning in Westminster, Carroll County | Maryland Planning Blog